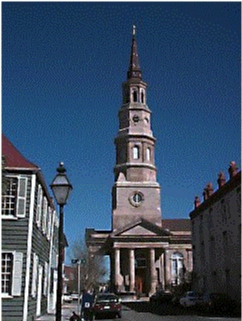

Note: This page is abstracted from www.ccpl.org/ccl/church_st_walled_second.html, and in the picture, the view is to the north down church street.

IMAGE: ON RIGHT --St. Philip's Protestant Episcopal Church, organized in 1680, is Charleston' s oldest Episcopal congregation and was the first Anglican church established south of Virginia. The first church, a frame structure, was built c. 1681 on the present site of St. Michael's at Meeting and Broad streets. According to tradition, the first minister was accused, in 1682, of having christened a young bear while in an inebriated condition. A second church was built in 1710-23, on the present site. Constructed of brick, the new church had a tower centered in the street, in the manner of contemporary parish churches in England which were placed at the center of crossroads. The church also had three Doric porticoes, which represented the first documented use of giant order columns in th American colonies. The second St. Philip's was describe by a contemporary account as "spacious, and executed in a very handsome taste, exceeding everything of that kind which we have in America." lt was built with funds partly obtained from duties on rum, brandy and slaves. The church caught fire during the great conflagation of 1796, but was saved by a black boatman who ripped burning shingles from the roof; he was sub sequently given his freedom as a reward. The building was burned to the ground by another fire in 1835. After the fire, the City attempted to widen the street at the expense of the steeple and porticoes. The Vestry countered that a fine steeple was more ornamental than a mere street. A compromise was worked out whereby the church site was moved slightly to the east, but with the street continuing in a curve around a projecting tower and steeple. The church was rebuilt in 1835-38. The Vestry asked architect Joseph Hyde to rebuild it exactly as it had heen. However, he pursuaded them to permit the replacement of massive Tuscan columns of the original interior design with lighter Corinthian columns, after the style of St. Martin's-in-the Fields, in London. The English Renaissance style steeple, in the Wren-Gibbs tradition, was designed by architect Edward Brickell White and built in 1848-50. The church bells were donated to the Confederacy to be melted down as cannon during the Civil War. During the Federal bombardment of the city, the steeple was used for sighting and the church was extensively damaged. It was also extensively damaged by the earthquake of 1886. ln 1924, the church was damaged by fire caused by lightning. The restoration, executed by architects Simons & Lapham, and completed in 1925, included the extension of the chancel by 23 1/2 feet, providing space for a new organ and choirstalls. The new construction was placed above graves and tombstones, so as not to disturb them. Many famous persons have worshipped at St. Philip's, including President George Washington, on his state visit in 1791. John Wesley, founder of the Methodist Church, preached here on his visit to America as a young man. Many prominent persons are buried in the churchyard, which is divided into two parts by Church Street. The Western Churchyard was set aside in 1768 for burial of "Strangers and transient white persons". The so-called "Strangers Graveyard" later was used for members of the church. The two yards contain the graves of John C. Calhoun, Vice President of the U.S. , Senator and cabinet offi cer; Rawlins Lowndes, President of South Carolina in 1778-79; Col. William Rhett, the scourge of the pirates; Maria Gracia dura Ben Turnbull, South Carolina's first known Greek resident; Edward Rutledge, signer of the Declaration of lndependence and Governor of South Carolina; several colonial Governors; five Episcopal bishops; Edward McCrady, the South Carolina historian; and DuBose Heyward, author and playwrite. Christopher Gadsden, the Patriot leader, is buried in the churchyard in an unmarked grave, at his request, according to tradition. An interesting pair of stones in the Western churchyard are known as the "Footpad's Memorial," and recite the story of Nicholas John Wightman, age 25, who was murdered by a footpad in 1788, and avenged by his brother, who rounded up the murderer and six accomplices, members of a gang who had "kept the inhabitants in constant alarm." The gates to the Western churchyard, installed c. 1770, along with the iron gates of the Miles Brewton House, are believed to be the only wrought iron gates surviving from the pre-Revolutionary period, in the city. The fence and gates of the Eastern churchyard date from 1826 and replaced a heavy brick wall and heavy iron gates with skulls and crossbones wrought in the iron work. The iron balustrade and portal gates set between the pillars at the west entrance to the church were possibly salvaged from the 1835 fire. ln the northeast corner of the Eastern churchyard is the old Parish House, an excellent Greek Revival structure.

(Legerton, Historic Churches , 18-19. ; Rogers, Charleston in the Age of the Pinckneys , 18-19. ; Ravenel, Architects , 163-165. ; Stoney, This is Charleston , 35. ; ______, News & Courier , April 20, 1958; Rhett & Steel, 40-41. ; Whitelaw & Levkoff, 75. ; Smith & Smith, Dwelling Houses , 31-33. ; Fraser, Reminiscences , 33. ; Severens, Southern Architecture , 56. )